“Won’t take no loss, won’t take days off

– From the hook on “Don’t Take Days Off” by Nipsey Hussle feat. Dubb (on Crenshaw)

We go so hard, until we fall

A n—a used to dream, my reality’s a dream now

I’m livin’ out my dreams now.”

Music. Every genre has its thing. Songs are often, if not usually, about something specific and structured accordingly. While every song is – in different ways – about the human experience, the tones, styles, and methods are different.

Classical and sacred music intend to keep us still, possibly pensive, and definitely focused.

Jazz musicians are about unexpected and unfamiliar rhythms, tones, and note pairings.

Country singers share heartbreak and relationship depth.

R&B and pop musicians touch on trends, feelings, and how they affect relationships.

Rock – be it light, classic, or hard – shares human emotion, sometimes with anger and always with candor.

Hip Hop, on the other hand, takes us to school. Like folk music and the gospel songs that preceded and led to it, Hip Hop tells us what is true. We may not like it or want to believe it. Too bad. We are hearing facts, not feelings.

Hip Hop was first reported by The Independent’s Christoph Hooton in 2015 as the world’s most listened to genre. Hypebeast shared in July that according to Nielsen Music, Hip Hop not only remains the world’s most popular genre, statistics indicate it is, for America, the favorite and most influential one.

The impact continues.

Hip Hop school has been in session via visual art since the New York City subway cars were aesthetically improved with tagging in the 1970s. The Hip Hop Museum is grateful and honored to present photographs, drawings, and paintings made by artists who choose to carry the torch, inform, and educate via their work. This choice is a heavy one because, for one thing, many of these artists’ portraits are of Black leaders, fighters, and visionaries who were murdered by police, competitors, and white supremacists.

Anyone with a pen and paper, or Photoshop, can deify Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Tupac Shakur, The Notorious B.I.G., and Nipsey Hussle by focusing only on the tragedy, grief, and rage brought on by their untimely, wrongful, and illegal deaths. To do that closes the circle. It ends their stories. There is no learning here, and there is no justice. There is only an image.

Brian Allen Irvin, born in Tyler, Texas and raised near Dallas, has been a visual artist and writer since the 1990’s. He tells stories by picking up the baton as a visual documentarian, operating the way MCs do with beats and rhymes. Irvin told me, “I’ve always felt compelled to honor the tradition of speaking to what I observe in the world to constructive ends, and I was put on the path – early in life – to hone a craft and learn to pair meaningfulness with visuals.”

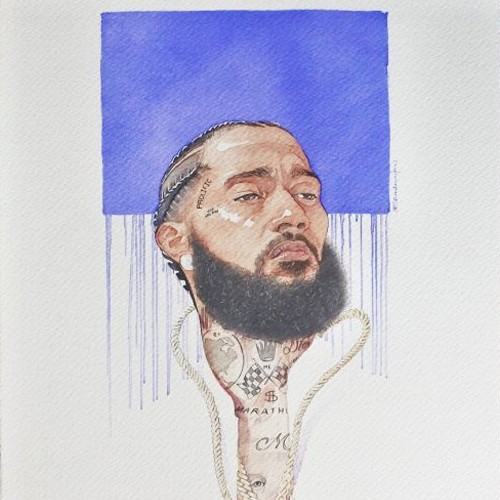

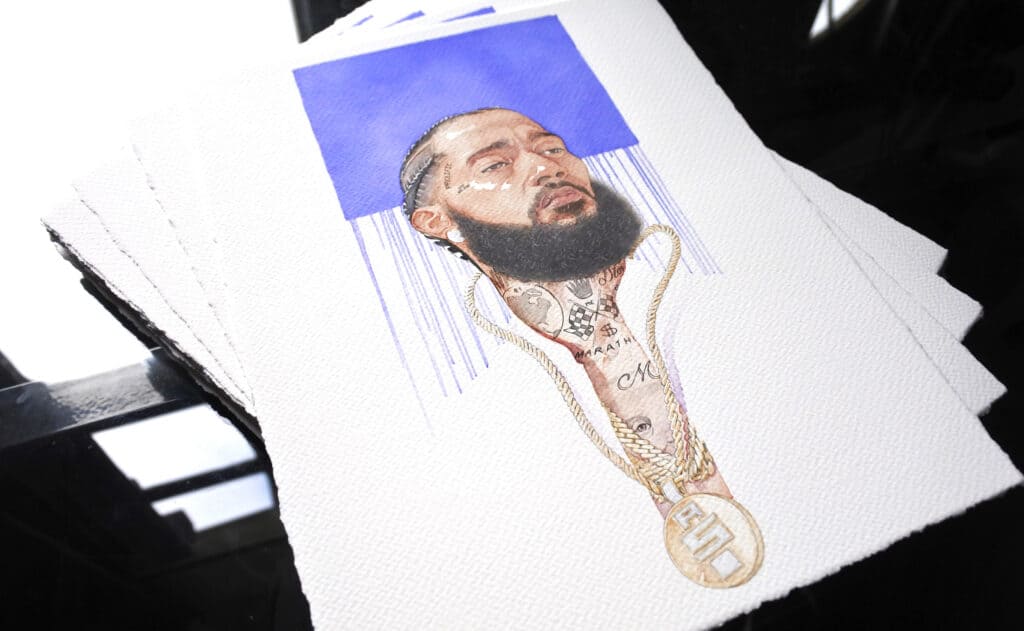

This author met Irvin after reading his appearance in the premier of a mutual friend’s brand extension. From there, I learned about him and his work. And the artist generously donated the picture above to the THHM, Ermias the Great. Read on for highlights from our conversations.

Brian Allen Irvin may have been born to make art. His parents acknowledged his interest and ensured he was exposed to as much as possible of what he calls “the craft.” The perceived glamour wore off quickly, as he comprehended how art could exist, and needed to, separately from entertainment. Early in our conversation, he said, “Art is so much more than how it makes you feel. It helps teach you how to think and not what to think. Your individual voice from your individual place in the world is invaluable.

”Irvin grew up with Hip Hop, and the music is “inseparable from [his] thoughts about the world.” As we discussed the effect of Hip Hop specifically on community and understanding as people, he asserted, “Hip Hop gives me the space to speak my truths unabashedly and with the courage of my convictions, in line with some of the firebrand Civil Rights leaders from our history. Hip Hop groomed my thoughts toward speaking loudly and outwardly about injustice and failures of the society.

”Music, particularly Hip Hop, fuels Irvin as an artist. He believes if you want to perform, produce, or make art inspired and empowered by Hip Hop, you must understand its spirit and why it is revered as it is. When asked why Hip Hop is so esteemed, Irvin announced, “There has always been plenty of awareness, around the world, about the Civil Rights Movement and how Blacks are treated in this country. Most recently, in response to George Floyd’s murder, the world stands in solidarity with Black people in America. Hip Hop, as it always has, exposes current conditions, and broadcasts that information globally. How this happens is aligned with art’s social function.”

As we discussed the joining of visual art and Hip Hop, Irvin’s response to my saying Hip Hop documents life differently (and more) than other genres was detailed and, well, accurate: “Hip Hop is the latest iteration in the tradition of Black music. Black music has always reflected on the Black condition in this country. Tonally, it’s confrontational and ignores the rules of ‘polite’ society decorum. and it has earned respect for that. It has a way of cutting through the bullshit like no other genre of music by balancing raw accounts with all the flair, disguise, and metaphor typical of art.

”For an artist to make something raw and unapologetic in its visual presence without alienating the audience is difficult. I asked Irvin what had he been taught that was unnecessary. Turns out he had heard what many young artists (myself included) are often told: to become fabulous, you must create, practice, and perform frequently. And like a true professional, he called hell no on that. Irvin declared, “I put a lot of pressure on myself, needlessly following the idea that I wasn’t getting better if I wasn’t putting pencil to paper every day. [And I would tell my younger self] do not feel the need to draw every day because technical skills are only part of being a good artist. Anytime I went stretches without working on art, it resulted in an imposter complex, because I felt I wasn’t serious or dedicated enough to be considered a real artist.”

Facts.

The imposter complex, or syndrome, is a challenge that afflicts many people on the come up. This internalized, psychological pattern is triggered when we doubt our accomplishments; we are afraid we will be seen as a fraud. Irvin’s methods to overcome it, and prevent it, are direct and simple: “Be patient and watch how you talk to yourself, because it all becomes clearer with time. The fulfillment in art comes from people accepting you for who you are, and always remember to have fun.”

Easier said than done, I challenged, when accepting one’s self as we truly are isn’t a piece of cake. Irvin was clear: “These – accepting one’s self and feeling accepted by people – are somewhat the same thing for the fact that accepting yourself precedes others accepting you. A positive feedback loop is created from that. It’s about being willing to speak without expectation of being understood.” He bolstered this when he told me, “As they say in American culture, racism is baked into the cake. Beyond the optics of cultural diversity, we have to get to a true diversity of ideas if we’re ever going to reach places where so many go unseen and unheard. We really can promote understanding if we embrace ourselves first, even with the pain and madness of being ignored as we are in this country. That’s a license to speak truth to power if I’ve ever seen it.”

And, that sounds like Hip Hop.

8” x 10” Digital Watercolor on Archival Cold Press Paper (photograph by Brian Allen Irvin)

Few people were as Hip Hop as the late Nipsey Hussle. Born Ermias J. Asghedom, he was murdered on March 31, 2019 outside his store in Los Angeles, the site-closed and now exclusively digital The Marathon Clothing. Besides being a bright star in the West Coast scene, Nip was an entrepreneur and an activist. His actions – releasing mixtapes and albums, founding his own label (All Money In) after leaving Epic Records, running his business in Crenshaw’s commercial district, including opening his store and buying the shopping center in which it was located, to provide opportunities for the neighborhood – and his music – such as “Bullets Ain’t Got No Name” mixtape series, “Dedication” on Victory Lap, and, giving Marathon Clothing customers access to exclusive music via an app created by 23-year-old digital architect Iddris Sandu – presented him as a revolutionary producer.

Producers tend to be trailblazers. They are architects of unexpected, unfamiliar, remarkable experiences. They are self-starters. “Nipsey had a relentless focus on self-empowerment,” Irvin stated. “For me, that is major because it’s not like our public school systems seek to create self-reliant, independent thinkers. So, it often takes a Nipsey Hussle to lay out the blueprint from a common sense stance.” I asked Irvin why he drew Nip and he told me, “What Nipsey did – in revolutionary ways – was show Black people (and anyone who was paying attention) how to liberate the economics in community, business, and the music industry. That a tatted, gold chain wearing, born in, raised in, living and working in the ‘hood Black man who did so much based on what he didn’t have and didn’t have access to, inspired, led, motivated, and mentored kids who weren’t likely to encounter anyone like him – ever – is truly tragic.” To address the grief and madness he felt when Nipsey was killed so senselessly, Irvin drew Ermias The Great. While his death is a painful reminder that tomorrow is not promised, he – and what he accomplished – is evidence that even with time cut short, real impact is possible.

It resonated hard with me that Irvin was the same age as Nip when he was murdered. We discussed how life is a blessing, a gift. When asked about the historical context of Ermias the Great, Irvin shared his insight from a favorite book, Huey P. Newton’s Revolutionary Suicide: “He talks about having to focus the efforts toward the established order, and how doing this doesn’t come from a death wish, but from the very human want to live with dignity. If it’s refused, you’ll have to force us out. It’s a reflection on the impetus that burns in every major figure you hear about come Black History Month. Any figure that concentrates their focus toward empowering a specific group of people tends to be hailed as a hero by that group. Nipsey very much falls in with that company for me.”

In other words, if we don’t feel that we belong, we can and will make a place and a space for us. Black culture, Black style, and Black music were, and are, born of this. Irvin cosigned when he stated, “Black art has never seen this level of elevation of popularity around the world as Hip Hop has seen. It lets me know there are ways to create appetites for stories that people would otherwise avert their gaze from.” The conditions from which Black and Brown people have historically come have not prevented accomplishments. In other words, subjugation has not prevented creation and innovation. Irvin staunchly said, “Hip Hop artists are the latest in the tradition of Black music to keep asking to be acknowledged as human beings that want dignity. That, combined with the destructive ignorance of the average American’s lack of historical context, tends to see Hip Hop artists as rebels without a cause because of it.

”Going deeper, while we talked about Irvin’s life as a Black man and his history as an artist, he declared, “Being Black and in the South, you have family that can tell you things as they’ve happened through the entire 20th Century up close. My lens on society has been shaped by those factors, and I strive for more universal themes to show up in my work as to how people allow, tolerate, and endorse the inequities in societies like ours.” He told me how frustrated he once was when white people diminished, or outright ignored, what Black people had to face, both historically and in the present day. I asked if his frustration was a motivating factor. Irvin replied, “The madness we accept in this society would frustrate anyone paying attention to it. Hip Hop, for me, is a powerful tool to amplify those issues, and I gravitate toward artists that acknowledge these issues in their work.”

Irvin’s favorite musicians and albums reflect this. His all-time favorite albums are ATLiens and Aquemini, made by OutKast, his favorite of the prolific Southern pairs. Irvin calls ATLiens’s innovative CD booklet, which is like nothing else in disc history, a “goddamn comic book.” He’d be correct.

Andre 3000’s and Big Boi’s unique ethos set a high bar, and thanks to a friend, Irvin connected Earth, Wind and Fire (of whom his father was a longtime fan) to OutKast via art direction flair and musical skills. Goodie Mob, the Dungeon Family, Swishahouse, ScrewedUpClick, and songs by Scarface (“My Homies”), UGK (“Ridin’ Dirty”, guesting on Jay-Z’s “Big Pimpin’”), 2Pac (“Me Against the World”, “All Eyez on Me”), and Geto Boys (“The Resurrection”) are pivotal in his musical memory.

For a man whose appreciation of musicians’ work needed to be earned, I knew Irvin’s list of the most significant albums would teach me something. While I tend to skirt superlatives, he did not: “I often make the argument for Kendrick Lamar’s good kid, m.A.A.d city being the greatest Hip Hop album of all time. To me, Kendrick Lamar is the most talented rapper of the era, and that album specifically reads like a stage play on a loop, itself a commentary of the cyclical nature of circumstance in this country particularly. The expression of environment (as acknowledged by the title), the moments of poor judgment as a young man and the reflection on them, the ability to communicate himself as a singular human facing the behemoth of environmental tripwires that the society at large has provided; it’s everything Hip Hop is supposed to be to me, and my experience hasn’t shown me anyone that has done it more effectively.”

Talk about Hip Hop taking us to school.

Learn more about Brian Allen Irvin and his work on his website, and follow him on Instagram. See more of his exceptional work, and look forward to seeing Ermias the Great in person at the museum (our groundbreaking occurred on May 20, 2021).

“Dedication, hard work plus patience

The sum of all my sacrifice, I’m done waitin’

I’m done waitin’, told you that I wasn’t playin’

Now you hear what I been sayin’

Dedication

It’s dedication, look”

– “Dedication” by Nipsey Hussle feat. Kendrick Lamar (on Victory Lap)