What do you do when you don’t agree with, approve of, or like something? Do you address it? Do you report it? Do you make efforts to correct or change it? When you know something that, or someone who, needs to be recognized and understood by people? Do you promote them? Do you share their stories? Do you celebrate them? And we’re talking about in life, not on social media.

Do you do what you can to let people know what’s happening, why it’s wrong, and how it can improve? Do you believe there’s real value in letting people know these things? Do you continue to share or broadcast what you know to be true, what needs to be addressed, and how to accomplish it until you’ve informed, encouraged, and rallied people to act?

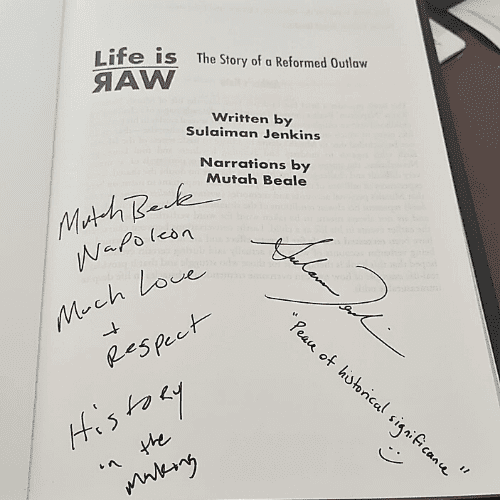

The book, which is highly recommended, leaves nothing out as it details Mutah’s life from an unimaginable tragedy to his conversion to Islam. To consolidate what happened over 20-some years diminishes the book’s significance and intent. This author was privileged to speak with Sulaiman and Mutah and learn how and why the book came to be, while hearing their individual and shared stories from the past and today. What follows here is a glimpse into not only the room where it happened (thank you, LMM), and why it happened from the perspectives of the narrator (Mutah) and particularly, the writer (Sulaiman).

Mutah and Sulaiman met in 2008, in Saudi Arabia. Before that, a lot happened (somewhat consolidated here for the sake of the readers’ time

and the aforementioned reasons).

And, so they begin.

If Mutah Beale’s name is familiar, there’s a good reason: As Mu, Lil Mu, and Napoleon, he was one of the Outlawz, a cadre of rhyme slingers from New Jersey, who performed with the late Tupac Shakur on several albums, and then did their own thing after Pac’s death. Mutah didn’t find Hip Hop as much as it found him. Few things are more raw and real than being three and a half years old, at home with your family in March 1981, and, with your two younger brothers, seeing your godfather murder your parents. It’s enough to live in Irvington, New Jersey’s most dangerous neighborhood, known for gang violence, drug dealing, and harassment by local police. To survive a murderous attack at your home only because the perpetrators ran out of bullets is akin to the “fact not fiction” at Hip Hop’s roots.

In Brooklyn, New York in October 1981, Sulaiman Jenkins was born. His life began, and continued, with only his mother and eventually, his younger brother. His father chose to leave the family before Sulaiman could crawl. His brother Qassim’s father also abandoned them. This rooted him, as it does many young men raised by one parent, to be the primary caregiver. That Mrs. Jenkins had Multiple Sclerosis (MS) made Sulaiman’s role as necessary for his family as it was instinctive to him.

Now orphaned, Mutah and his brothers Mumin (who is now called Moon) and Kamil (who today goes by Mill) grew up in the home of their father’s mother, Grandma Mary, and his sister, Auntie Samira. Also in the house were the boys’ cousins Roddy and Reef. Mutah credits Reef with his introduction to Hip Hop, its culture, and its style. While the family wasn’t impoverished, Moon and Mutah did their part to contribute to the family’s coffers by dealing drugs. As Mutah told me, “It’s what everyone was doing, honestly.” It was almost intrinsic in the community, because you must do what’s necessary to survive. To survive in Irvington, New Jersey was to know how to live where graffiti, organized gang activity, gun carrying, police patrols, drug dealing, and the arrival of crack cocaine are as present as traffic. When crack arrived in the neighborhood, Mutah and Moon were between eight and nine years old.

Growing up in Brooklyn in the mid- to late ‘80s, in a neighborhood which was then known – not thought – to be dangerous due to rampant crime, assaults, and gang activity, Sulaiman learned how to look out for his family while living the life of an 11-year-old in Brooklyn. When he and Qassim (age 10) walked home from school, it was a fairly regular thing for them to be accosted for their JanSport backpacks. The backpacks’ contents? Books. Sulaiman woke up at 6am every day to take his brother from their house in Crown Heights to their school in Bushwick, which was at least 45 minutes via subway. 10- and 11-year-olds riding the subway by themselves happened because there was no parent available to accompany them. Their fathers had long ago abandoned their family. Mrs. Jenkins had stopped working, due to her MS, in 1989. Sulaiman became, and remained, the man of the house for all responsibilities, tasks, and supports.

Growing up by living grown people’s lives.

In 1993, Sulaiman, one of the top students in his seventh grade class, received the application for PREP for PREP’s PREP 9, an extremely selective program that helps the brightest and most promising Black and Latino students in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut prepare for boarding school matriculation. He applied, and was chosen. His life as a pre-adolescent was finished: no more free time, afterschool hangouts, or activities with friends. Everything in life, other than looking out for his mother and his brother, was academic.

After 14 months of – for all intents and purposes – going to two schools, with PREP 9 assigning more homework than Philippa Schuyler IS 383 did, requiring attendance during the school year, Monday through Friday between 9am-5pm during the summer, and every Saturday during eighth grade, Sulaiman was ready, willing, and able to take on the most challenging high school experience. This presented itself in the form of St. Andrew’s, one of the most elite boarding schools in the US. He wanted to enroll there for the intellectual work, and for the increased opportunities to “secure the best job once [he] went to a good college.”

Underscoring every class attendance, afternoon activity, and athletic practice on the Middletown, Delaware campus was “the pursuit to make a better life and lots of money, because [his] mother was sick with MS and could no longer work.” Attending this school (1995-1999) was also part of Sulaiman’s dedication to show his friends that it was possible to make it out of the ‘hood via education which, in a world where the ambitions to work in sports and entertainment were paramount, was rarely, if ever, considered, let alone done.

Upon graduating from St. Andrew’s, where his accolades included scoring 1000 points in senior year basketball (a first in the school’s history) and being the second best scorer in the state of Delaware, Sulaiman attended Amherst College, one of the most prestigious liberal arts universities in the United States.

1993 marked the start of a new chapter in Mutah’s life as well. While he wrote the chapter, its components were provided by his family, specifically his cousin Reef, and friends who had become family. As crack was destroying lives, rap music was doing the opposite as it made its way through Black communities, including Irvington. Hip Hop and family kept Mutah up. Bolstering Grandma Mary’s loving household was the presence of Aunt Beatty (Mutah’s father’s sister), her daughter – cousin Talibah – and Talibah’s friends Yaasmyn Fula and Dana Owens (known today to the world as Queen Latifah). As family is wont to do, Aunt Beatty invited Mutah, Moon, and Mill to her house in Montclair, New Jersey often when Talibah’s friends, specifically Yaasmyn, were over. Montclair, relative to Irvington, was lush, verdant, and welcoming. Coupled with the warmth and support of the home and real friends, and becoming close with Yafeu, Yaasmyn’s son, Mutah was happy, yet still felt very empty.

Cue Reef and the music he shared with Mutah: Run DMC, A Tribe Called Quest, Slick Rick. Mutah felt the rhymes and beats, and was fascinated by how the lyrics were made. He began to write his own raps. Seeing Jersey-born and -raised Queen Latifah on television and hearing her on the radio inspired him. With all of the anger Mutah felt, and it had been building since age three when he watched his parents be shot to death, he found relief in rapping.

Like the gospel music and jazz that preceded it, Hip Hop provided Black people a method to message their feelings, their stories, their truths. In 2018, Nielsen reported that Hip Hop was the most popular genre of music around the world; nearly 30 years ago, it was something that spoke and stood for Black people unlike any art and media forms in decades. It spoke to Mutah, and initially he modeled his raps after ATCQ, Run DMC, LL Cool J, KRS One, and more. Their rhyme skills were on point. Their topics, on the other hand, did not resonate with Mutah: he didn’t party and joke and have fun. The rawness he had known and lived since he was a toddler was his life. The band that lifted Mutah from his everyday was N.W.A. Their uncompromising style and lyrics resonated. And Mutah’s first song – “Money and Murder” – was born of hearing men from Compton broadcast their truth. He knew the streets, and he wrote them. He was 14.

It wasn’t long before the neighborhood, including drug dealers and OGs, knew, sought, and heard Mutah. Ever the entrepreneur, when people asked him to spit rhymes, he said “This is a business. I gotta eat.” And the dollars rolled in. Gone was the slingin’: Mutah swapped crack vials and dope heads for rap bars, beats, and hooks. He also swapped his academic education for spitting rhymes and being – for lack of a better word – developed as an artist (and a profit maker) by neighborhood hustlers (Corey, “C”, Shalaby, Rab, and Mike aka El Niño, neighborhood friends with lyrical skills (Bre and Hak AG), and music producer and childhood friend Jamil. Eventually, he had an entourage, he improved his rapping, and people in and outside the Irvington area noticed.

Things in the arts – and in the ‘hood – can move quickly. After an unsuccessful audition at the Apollo Theater, Mutah reconnected with Yaasmyn when he was visiting his cousin Talibah. As they caught up and he told Yafeu’s mother about his entry into Hip Hop and accompanying ambitions, she shared a wild coincidence: turns out Yafeu was also trying to get in the rap game. Yaasmyn suggested Mutah reconnect with her son. That could happen soon, as she was heading to New York where he would be staying with his godbrother: Tupac Shakur.

Truly, there was not a better artist for Mutah to meet. Besides the socially conscious, street-driven messages in Pac’s songs, his mother Afeni was a member of the Black Panther Party. Ms. Shakur met Yaasmyn via the Panthers and they became close, leading to Yafeu and Tupac becoming godbrothers. Ms. Shakur not only gave birth to her only son one month after her acquittal of conspiracy charges by the US government, she imbued him with warrior style, activism, and a revolutionary approach to everything. Mutah’s first meeting with Pac and crew, and what followed their meet, is described thoroughly in the book. Suffice it to say, the game changed when Mutah, now 15 years old, shared with Pac (also fatherless) how his parents were murdered.

So, after years of behaving as was necessary to live in the ‘hood – as a crackhead or a drug dealer – and walking a tightrope of attending school and slingin’ (selling drugs, which in this case were vials of crack) on the street, being arrested at age nine, getting expelled from school, witnessing childhood friends be killed over gang fights and drug deals gone wrong, and missing death himself, Mutah moved to Atlanta. The ways to ATL were via truth and Hip Hop. Officially, Mutah had begun to rap his way out the ‘hood.

Straight outta fairy tales, until real life takes hold.

Sulaiman’s first year of college, spent primarily in bucolic Western Massachusetts with trips to Maine and Vermont, began in autumn 1999. Adjusting to the fairly arctic winters is all he thought he’d have to adjust to, with four years of conservative boarding school completed. As modern and progressive as Amherst claimed it was, Sulaiman’s matriculation was closer to “Higher Learning” and a right wing version of The Preppy Handbook. First, this most sought after student – due to his basketball skills – who had opted not to go Division I, who had dedicated himself to the game so he could manage his emotional and mental anguish, who made it on the college team during his first year, was benched for nearly every game, every season. His primary activity and conduit were gone. Add to that, during the summer between his sophomore and junior years, Sulaiman recovered as much as he could from the untimely death of his St. Andrews roommate and close friend, Christopher Wilson.

Life’s fragility, of which he was always aware, became a focal point in Sulaiman’s life while he tried to handle his friend’s unexpected death. These, along with dining hall segregation, an exclusionary student body, and the covert racism of New England, moved Sulaiman to coping strategies familiar to many of us: drinking and a variety of drugs.

Before he graduated, Sulaiman kept things busy and focused professionally with his summer internships, beginning in 2000 with a role as a paralegal at Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson in Manhattan. The following summers saw him first at Salomon Smith Barney in asset management (2001), and as an analyst in risk management at Deutsche Bank in 2002. While the economy and market trends had changed, the Gordon Gekko life hadn’t: the 70-hour weeks with zero free time all but encouraged drinking and drugging to help him get by. Sulaiman’s income, along with the culture and nature of two of the industry’s heavy hitters, encouraged and facilitated these actions.

As unexpected as it may be, sometimes our darkest times lead us to better paths, or at least better methods. For Sulaiman, between the loss of Christopher, not playing basketball, and his active coping mechanisms, he arrived at a crossroads while working at Deutsche Bank. In summer 2002, he realized how unfulfilled he was, despite the impressive, high-paying, intellectually challenging job with complete access to a world of temptations. When the towers fell not quite a year before, Sulaiman had not considered returning to the practice of Islam. He felt shocked by the actions, and he did not align the terrorists’ activity with the religion. While his office at SSB was in one of the Twin Towers, he was not there when the towers were attacked. What moved Sulaiman first to the notion of being Muslim, and then to the practice of Islam, was the realization that without significant change, his mental, emotional, and spiritual health would completely deteriorate.

Neither psychiatry nor meditation, not reggae music, and definitely not yoga provided the structure and spirit he needed. So Sulaiman went back to what felt good and true without the seasonings of drugs and alcohol, which he had come to rely on every day. Once he identified that a return to his Muslim core would provide the daily structure and life principles he needed, Sulaiman wholeheartedly accepted it. Since then, he has not looked back. He said, “When I returned to my Muslim roots, I had purpose. Besides looking after my mother, my life was spent in the service of God, doing good for people, and living in positive ways. Life finally made some real sense.” All the tangible and social benefits of working in finance did nothing but burrow a hole in Sulaiman’s spirit; Islam filled this void. It was so meaningful, that when Deutsche Bank offered Sulaiman a full-time salaried position upon graduation, he politely declined it.

In Atlanta, Mutah was living the life: the family Hip Hop had made possible – Pac, Afeni Shakur, K-Dog and his mother Gloria, Big Malc, and Yafeu (aka Young Hollywood) – was welcoming, inclusive, and generous. The 16-year-old’s lyrics so impressed K-Dog, Young Hollywood, and Big Malc (the forerunners who, with Mutah (called Mu and Lil Mu), would become Outlawz), his words laid the foundation for their first song. Pac heard it, cosigned it, and named them Dramacydal. He would go on to record it with them. (Note: the song, “Killing Fields” feat. Dramacydal, was recorded in 1994 and never released by Interscope Records; after Pac’s death, musicians and DJs made it heard on loads of mixes and playlists. When you can, hear it. Appreciate it.)

The events that followed in Mutah’s life, some known to the world and some not, are best experienced via the book, either read or heard. They include:

- Pac being shot five times in the lobby of Manhattan’s Quad Recording Studio,

- his incarceration following a guilty verdict for alleged sexual assault,

- the East Coast-West Coast rap beefs and subsequent media exacerbation,

- the Outlawz each getting their names changed by Pac (Mutah became Napoleon) to reflect the Machiavellian nature of the genre, Pac’s belief in The Prince (evinced by his artist name change to Makaveli), and the unapologetic, untrusting, and battle-ready nature of gangster rap arrival in the public domain,

- the move from Interscope Records to Death Row Records,

- Pac’s being shot in Las Vegas, and his homegoing six days later on September 13 1996.

- Death Row’s eventual release of “The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory”, which sold millions in its first months, many of whose tracks featured the Outlawz,

- the label’s mogul Suge Knight was sentenced to nine years in prison for a parole violation,

- Christopher “The Notorious B.I.G.” Wallace died on March 9 1997, after being shot four times in Los Angeles,

- the Outlawz departing Death Row in late 1999 thanks to Afeni Shakur’s efforts,

- Interscope and Death Row, in collaboration with Amaru Entertainment (Afeni’s company), releasing “Still I Rise”, which included the Outlawz as much as it did Pac,

- the Outlawz opening their own record company (Outlaw Recordz) in 2000 where they produced their debut album, “Ride Wit Us or Collide Wit Us”,

- the group founding Outlaw Clothing, giving Mutah his “first taste of entrepreneurship”, and from that,

- the group meeting the highly sought and much respected talent manager Steve Lobel, who introduced them to industry leaders and whose presence gave the Outlawz additional music cred.

Besides those occurrences, one month after Pac died, Mutah was arrested in New Jersey, Grandma Mary died, Kadafi (also known as Yafeu) was accidentally shot in the face and killed by Mutah’s cousin Roddy, and his cousin Seike killed himself. To manage his grief, Mutah drank and raged. In a fight with his brother Mill, Mutah punched him so hard and so many times, who knows what might have happened had cousin Reef and others showed up to restrain him. Mutah committed to sobriety upon the recognition of his brother’s blood all over the room, and all over him. His awareness and acknowledgement of Islam followed shortly thereafter, as did his commitment and conversion to it. Chapter 15 in the book presents this in all of its depth and complexity.

While they were on opposite sides of the country, this author’s not believing in coincidence shows up in the acknowledgement of the nearly simultaneous realizations that comfort, clarity, and answers were present in Islam. What Sulaiman and Mutah already shared – growing up without parents, carrying adult responsibilities before being of age to drive, vote, or drink, experiencing rampant discrimination and the inherent racism that may as well be weaved into the American flag, and being dedicated to Hip Hop’s activism as much as its artistry – laid the groundwork for them to, at some point, work together. This eventually happened, thanks to a mutual friend.

Moving up means moving west.

Sulaiman attended New York University Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development for his Masters Degree in teaching English as a second language (TESOL) in fall 2003. Before that began, he realized he wanted, and needed, to continue his spiritual fulfillment by going to Saudi Arabia and being near Mecca and Medina. He chose TESOL on the suggestion of a friend, who had shared that people who taught English to Saudi youth were in high demand, their salaries were tax-free, and paid medical and housing expenses were included in the salary. Recall that Sulaiman had turned down Deutsche Bank’s offer to work there permanently after graduation; he needed something that was – for him – truer and deeper. His first teaching job was in Dammam, September 2004. He moved to Riyadh in 2006 and worked there for 12 years, moving quickly up the ranks in academia to a role as a course supervisor at King Saud bin Abdulaziz University. Between 2018 and mid-2021, he was the English Department’s Lecturer and Coordinator at King Fahd University in Dhahran. As always, he used the academic and intellectual platforms to rid teaching of the English language of its racist and discriminatory practices. His work extends beyond the university, and appears via routinely published scholarly articles and international workshops.

Before Mutah moved permanently to Saudi Arabia in 2010, where he would make an entirely new life, he closed the door on his impressive life in the music industry by doing something significant. He wrote “What’s Wrong”, a song on Darryl ‘DMC’ McDaniels’s award-winning solo album “Checks, Thugs & Rock and Roll”. He declared, “Having listened to and watched RUN DMC, who were legends and pioneers, when I was growing up, and Tupac respected them, it as a dream come true.” This was the last thing he would do as a musician because upon converting to Islam: Mutah “found what [he] hadn’t in the music industry with women, with drinking and drugs.” And it was more than finding peace through practicing Islam: “Before this,” he stated clearly, “I hadn’t cared about living or dying, and I hadn’t, since getting involved in the street life. When I saw the darkness, I gave up. To be honest, after losing Tupac and Kadafi, I lost all hope.” Prior to his move, in 2006 (and continuing today) he participated in public speaking engagements around the US, Europe, Australia, and Africa talking about “life in the ghetto” within the context of being an entertainer. He digs deep into youth violence, gang life, and urban life. Mutah has found the audiences are “more prone to listen to an ex-rapper than people in their own neighborhood.” In his talks these days, he discusses his complete denunciation of extremism in Islam, his life as a Muslim, and how this life is better than those led by gang members, drug dealers, and rappers.

As he was preparing his family to move permanently to Riyadh, the country’s capitol, in 2010, Mutah’s son Muhammad was diagnosed with neuroblastoma. This changed his perspective on life. He thought when he became Muslim, he would be distanced from tragedy. And for his son to be diagnosed with cancer showed him that he wasn’t special where trauma and tragedy is concerned. Muhammad was treated and the move was delayed until he was cancer free. Once his family was moved, Mutah wanted a different, more peaceful environment, an Islamic environment, and a good place to raise children. He didn’t know anyone, yet with the brotherhood of Islam, and people’s welcoming natures, he “didn’t really feel like an outsider.” Mutah took Arabic classes at the university, acclimating to life in Saudi Arabia, and enjoying gatherings at the homes of Muslims.

Stepping back in time a couple of years to Riyadh in 2008: Sulaiman and Mutah met via their mutual friend Kashif Nuriddin, who invited them to join him for a meal. Over dinner at El Chico (because every city around the world has at least one really good Latin American restaurant), they clicked and occasionally spoke over the next few years.

In 2015, Sulaiman reached out to Mutah, asking how he was and what was going on. A lot had happened since they dined in ’08: he partnered with a friend who had a coffee shop to learn about the business as an investor. Mathaq Alkayf was open for about a year, and its creation and existence led to Mutah building his own coffee brand: MW Café, which began in 2015 with a mobile truck and a bus parked at Al Faisal University. (Now brick and mortar, MW Café is located in Riyadh City’s Al Nafl Area, and the second location is currently under construction.) He shared all of this with Sulaiman when they got together over gyros in Riyadh. What had clicked in 2008 was now officially in process, and their friendship began to flourish.

Take the facts. Make a book. Tell a story.

Before he and Mutah became brothers, Sulaiman knew the Outlawz, having been audibly introduced to them by Tupac Shakur. Before he became a fan of a group made up of men who were his age, Sulaiman shared, “The one who taught me the most via their songs was Tupac. He helped me understand what it is to be Black and to love myself.” Where the Outlawz were concerned, that they were “young and raw” made their tracks about being brave and tough as applicable to an all-white boarding school as they were to life in the ‘hood. And, due to his rhymes, which truly spoke to him, Mutah was Sulaiman’s favorite of the Outlawz.

Have you ever become friends with someone you really admired? Someone for whom you were a true fan? It rarely happens, and personally, I don’t know what I’d do were it to happen in my life. Once Mutah and Sulaiman were friends, and their trust was mutual, Sulaiman invested in thirty3, Mutah’s urban-inspired clothing line. So, Sulaiman had gone from fan to friend, from friend to investor, from investor to advocate and author. Right? Not yet.

When Sulaiman saw an Instagram comment on the Thirty3 account saying “We’re waiting for your book,” he floated the idea: they could – together – write a book about Mutah’s life. The potential subject was rightfully cautious, because a book that was released in 2012 had not been a positive experience: it was written by a friend of Mutah’s. Authors weren’t on his list of trusted people. Not to be thwarted, Sulaiman showed him some of the material he’d written for Oxford University Press, because “evidence provides reason to trust”. Mutah read one of these papers, and it was on.

As much as they need trust, and content, effective books also require the ideal style, tone, and formatting to attract and sustain readers, and have impact. When writing about people who have been in the public eye, particularly in our world of social media and really short attention spans, authors need more than excellent writing skills. They need the best intentions, and permissions. Permissions meaning permission from the subject to leave out nothing, and spare no details. Also, permission from the author to be willing to push the subject to really leave out nothing. Sulaiman received and provided permissions.

It’s not easy to write one’s own story for the world to read and hear. It’s not easy to write a friend’s story for the world to read and hear. Why? Because to be vulnerable and share what was done and what happened after trauma requires courage, nonstop courage, because you don’t honestly know if anyone is going to read or listen to your life and its lessons. And after you give permission, you have to be willing to share what, at the time, felt ugly, shameful, and embarrassing, particularly if it feels like that today. There’s nothing rawer than what actually happened and you felt about it. While they didn’t say as much to this author, Mutah and Sulaiman knew all of this. Their book is the evidence.

When asked why he structured the book the ways that he did – starting with shock, including major events in the United States, not always chronological – Sulaiman was thoughtful: “From the first chapter, life is raw, that was – and is – Mutah’s life. I surrounded the major events in his life with what was happening in the US to document in ways that are as much emotional as they are historical.” This choice supported his goal to make something meaningful and important “for the Black community, the Muslim community, and people in the United States.” And the “something” needed to be “inspirational and a blueprint for people who experienced trauma.”

As we discussed that the audience for their book was likely more than Black people and Muslims, Sulaiman concurred. He wrote for scholars, sociologists, researchers, criminologists, psychologists, mental health counselors, Hip Hop fans, people who loved Tupac, fans of Mutah around the world (particularly those who are unfamiliar with urban life and Black culture), fans of Mutah who are Muslim and unaware of why he converted to Islam, people interested in religious studies, and celebrities who experience personal trauma “to see how they are not alone when they actively face their traumas, which Mutah did before, and since, he found Islam.”

Noting that the media was not included in the list of target audiences, Sulaiman confirmed it. Regarding, for example, the coverage of Tupac’s and Biggie’s murders and the active (or thoughtless) ignorance that underscored it, he declared, “With their deaths, the media took every opportunity to say ‘See, what did we tell you? Gangsta rap and rap in general are garbage, and the people who make them are trash.’ The media frenzy was wrong and detrimental. For the police in Los Angeles, New York, and Las Vegas to have so much evidence and be told by city politicians to investigate only at a surface level, of murders of an icon and one who would soon be known as an icon makes their murders more tragic.” His points are well taken: to this day, both cases remain unsolved, and around the United States, examples of how police and the legal system fail to serve Black communities are too frequent to count.

Authors either love or loathe to be asked what it meant for them to write books that are important to them personally. When asked this, Sulaiman initially struggled, as people who are not spotlight seekers tend to do. Ultimately, though, he said that by writing Life is ЯAW, he could accomplish several things. He was direct: “Personally, I don’t think there are books out there that present life in the ‘hood, with all its traumas, in ways that are accurate that will be accepted – and celebrated! – by the people who live and lived what’s being discussed. People who’ve lived posh lives and write about ‘hood life is like a body with no soul.” He turned his statements inward, for a moment, when he professed, “For a person who grew up in the ‘hood who went to impressive schools can show what can be done, that’s my responsibility. And it’s important for me that people know it’s possible grow up in the ‘hood, without a father, and do this.”

“This”, of course, is more than author a book and get it published. “This” is deciding, choosing, and actuating what has been told and shown to you to be impossible in all ways officially, publicly, and globally.

In the book, Sulaiman chose to provide examples of trauma, tragedy, unbelievable deaths, and violence throughout the book. That its last chapters speak to and present guidance and enlightenment was a decision fueled by author knowledge as well as the fact that Islam was, and is, a stabilizing force for Mutah and those who are aware of its tenets, traditions, and scriptures. Social activism is possible via faith and religion, in ways similar to music and visual art. Today, neither Sulaiman nor Mutah follow and listen to Hip Hop. When asked how the music and the movement were important to him back in the day, Sulaiman replied that without a father who could provide “a road map for what it means to be a Black man in the ‘hood, and this world,” Sulaiman – like many of us – looked to and leaned on music. Hip Hop, like hymns and spirituals, protest music and spoken word, is rife with rhymes that comfort and guide us. For Sulaiman, when he listened to Hip Hop, he recognized “it was powerful in how it expressed how I felt, and how society viewed me, as a Black man. It presented our narratives in accurate ways while we didn’t – at the time – have control over labels and media.”

Life is ЯAW: The Story of a Reformed Outlaw reclaims a narrative and control over labels and messaging.

Were Sulaiman and Mutah average people, and there was no book, their story might go on to be one where Mutah becomes a world famous Hip Hop solo artist, Sulaiman goes on to be a highly paid Wall Street macher, and everyone keeps moving. These men are not average people. Whether it was fate (which this author does not believe in), coincidence (again, not a real thing), or happenstance (also not possible), Sulaiman and Mutah moved the needle, for the betterment of everyone around the world with their first book. Via its tone, content, and intentions, this book was produced in the ways of foundational Hip Hop. Sulaiman described and defined this music: “expressing what it is to be – and what it means to be – Black, and to struggle on the daily. It was, and still is, currency, and it serves as a voice for what Black Americans go through.”

While neither of them is in the music industry today, each is creating, curating, and leading. Both of these polymaths have a lot going on. Check out Mutah’s cafés and coffee, his clothing line, his foundation, and follow him on Twitter and Instagram. Sulaiman is on Twitter, Instagram, and Google Scholar. To read the book, it’s available here; to hear the book, pick it up here.

And, we created a playlist of resonant and relevant songs by 2Pac and The Outlawz to accompany this interview. Hear them on your preferred music platform:

The Outlawz

“You Can Be Touch”

“Letter 2 the President”

“Who Do You Believe?”

“All Out”

“Starin’ At the World Thru My Rearview”

“Lost Souls”

2Pac

“Dear Mama”

“Keep Ya Head Up”

“White Man’z World”

“Hellrazor”

“So Many Tears”

“Holler If Ya Hear Me”